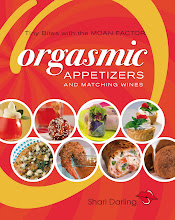

Products from Niagara Vinegars in Niagara, Ontario

Niagara, Ontario

Niagara, Ontario

Niagara, OntarioWine vinegar has many places in the culinary world. Vinegar derives from the French word, “vin aigre”, meaning sour wine. Many commercial wine vinegars are made from cheap wine. Stainless steel tanks are filled with wine and bacteria. Compressed air is blown into the tank, causing the “acebacter” or bacteria to eat the alcohol and turn the wine into vinegar.

In commercial processes this can take place from three hours to three days. Quality wine vinegars take time to produce, however. Quality versions are made through the “Orleans Method,” originally proposed by Louis Pasteur. Named after the French city of Orleans, this process provides three main ingredients – food (the wine), air and a dark, warm environment (oak barrels). Oak barrels are filled with wine, then inoculated with an actively fermenting vinegar. Taking from nine months to a year, the wine slowly turns to vinegar, all the while developing complex flavours.

While of French decent, the Californians have capitalized on this concept of “varietal” wine vinegars. This means the vinegar is produced from a specific grape variety. For example, Chardonnay Vinegar is produced from the Chardonnay white wine, made from the Chardonnay grape. Cabernet Sauvignon vinegar is made from the varietal wine called Cabernet Sauvignon, deriving from the same red grape.

Many food and wine lovers assume that Chardonnay wine would be a perfect match for a salad drizzled in a “Chardonnay vinaigrette." After all, both are made from Chardonnay grapes, obviously possessing similar flavours. Right?

Not quite. It's not quite that simple because it's important to harmonize the taste sensations of each, not the name of the grape on both bottles.

The primary building block in Chardonnay wine and in Chardonnay vinegar is acidity experienced on the palate as tanginess or sourness. That’s good. BUT …vinegar is more sour than wine. The vinaigrette's overpowering acidity makes the wine’s acidity occur as flat on the palate. The wine tastes flat, thus losing its refreshing quality. Said more simply, vinegar overpowers wine.

For the combination to harmonize, the wine should offer more tanginess or acidity than the vinaigrette.

Pairing Chardonnay wine with Chardonnay vinaigrette can work, providing you use the vinaigrette sparingly and incorporate proteins into the salad, such as cheese, nuts and/or flesh (chicken, ham). By doing this you dispurse and decrease the intensity of the vinegar in the salad, allow the wine to remain MORE sour.

Pairing Chardonnay wine with Chardonnay vinaigrette can work, providing you use the vinaigrette sparingly and incorporate proteins into the salad, such as cheese, nuts and/or flesh (chicken, ham). By doing this you dispurse and decrease the intensity of the vinegar in the salad, allow the wine to remain MORE sour.

If the wine vinegar uses with other ingredients like fruit, then be sure to look at the overall sweetness level. If the vinaigrette is sweet, then consider pairing the salad with a wine possessing some sweetness, such as a semi-sweet Riesling. Again, make sure the wine is more sweet than the vinaigrette.

Niagara Vinegars based in Niagara produces a wide range of wine vinegars fused with other fruit flavours, such as peach chardonnay, raspberry baco noir, and juicy orange vidal. Consider the sweetness level in these vinegars to choose the appropriate wine. This company produce some of the most delicious vinaigrettes I've tasted.

The point is that considering the taste sensations of the wine and the vinaigrette is more important than marrying the grape variety used in both.

Niagara Vinegars also produces rice wine. Rice wine is far softer than white or cider vinegar and is the ideal product to incorporate into a vinaigrette that is being married to wine. A salad drizzled in rice vinegar is the perfect partner for Pinot Gris.

My favourite vinegarette made by this company is Ruby Red Grapefruit. It is juicy and outstanding. Every time I serve this product on salads for guests, I'm forced to give the bottle away. This vinaigrette is a crowd pleaser. You don't need a lot to make your salad taste fabulous.

It's a little tart for wine, so be sure to add some proteins into the salad like toasted peacans to have it pair with wine. Marry salads in this vinaigrette to crisp, dry white wines, such as Sauvignon Blanc and dry Riesling.

I purchase my Niagara Vinegars at Firehouse Gourmet in East City, Peterborough. However, the their products are available throughout Ontario and Canada, I believe. To find out where the vinegars are availabile in your town or city go to: http://www.niagaravinegars.com/ or call 905-685-0385.